The (much quieter) banking panic

by Jerome a Paris

Thu Sep 25, 2008 at 03:37:55 PM PST

The Financial Times is (rightly) worried:

Banks are not to be trusted. This is not just the view of the public and policymakers, but that of the banks themselves.

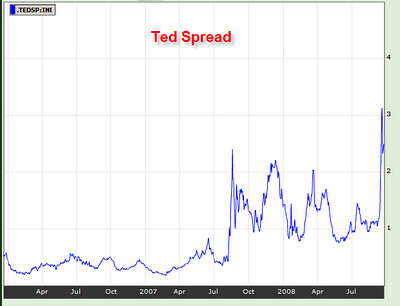

And indeed, the most notable thing over the past year has been the general mistrust amongst banks, and their reluctance to lend to one another. This graph shows a direct indicator of the level of defiance between banks:

Via Mish

- Jerome a Paris's diary :: ::

The TED spread can be used as an indicator of credit risk. This is because U.S. T-bills are considered risk free while the LIBOR rate reflects the credit risk of lending to commercial banks. As the TED spread increases, the risk of default (also known as counterparty risk) is considered to be increasing, and investors will have a preference for safe investments.

As the FT notes:

If lenders demand huge spreads for such short periods, they are either tightly constrained in their ability to lend, deeply concerned about the solvency of counterparties, or engaged in predatory behaviour. Whichever of these possibilities is true, credit to the economy will dry up.

As someone noted a while ago, banks started looking at their balance sheets last August, suddenly decided they did not like what they saw, and went through the following process: "we've been wiser than others, so if our balance sheet stinks like this, we don't even want to know what those of other banks look like - but we'll stop lending to them." Interbank lending froze up then, and has never really recovered - it just gets worse at each new seizure of the markets, and the current situation can only be described as critical.

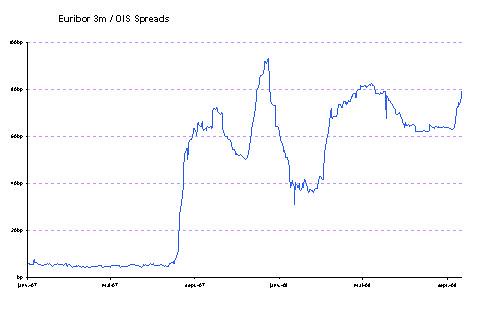

This one shows what's happening with euro bank credit risk

Banks are hoarding all the cash they can (avoiding new deals, not renewing facilities that come to an end and would in normal times be extended, and now even trying to find legal - if not necessarily very proper - ways to sneak out of existing commitments), both because they need it for their own basic needs, and because they simply don't trust the risk represented by other banks.

And given that at any time a bank makes a loan to a customer (at least for big corporate deals), it borrows the same amount of money on the markets, the fact that the interbank market, ie where that borrowing part takes place, is frozen can makes it difficult for banks to continue with the lending.

Those that still have access to liquidity are paying an increasingly high price for it (the above represents the price the best banks have to pay - it's even worse for most others). Others have to make do with ultra short central bank liquidity lending. but you cannot run your ordinary lending activities (which rely on 3-month or 6-month funds) on overnight funding at punitive rates.

Thus, credit to the economy is drying up. Corporations often had a good balance sheet, and lines of credit that were available to them at good conditions, but these are either used up or expiring as time goes by, and they are no longer renewed, and the pressure is building up for companies also to start scrounging for cash.

In the financial world, this is bringing about a grand de-leveraging (ie the infamous tide that supposedly lifted all boats is moving out rather brutally, and we're seeing, to mix maritime metaphors, who was naked under the water).

- The players that had low risk, low cost funding, high volume investment strategies are stuck as the low cost bit has disappeared; they have to stop their business; some have come to trouble in the process, but this is a liquidity issue and they might be saved by central bank intervention;

- those that had high risk, low cost funding, high(er) returns are quite dead as the high risks happen to have been (really) bad risks. The disappearance of low cost funding is, to a large extent, irrelevant to their situation.

The trouble is that the two cases are often hard to distinguish, because they are engaging in the same behaviour: they are trying to sell assets: in one case, to reduce their (now expensive) borrowing requirements, in the other to raise cash to plug holes in their balance sheet or to get rid of the toxic stuff.

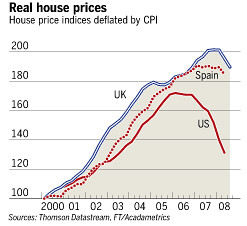

And banks have realised that, in the best case, they belong in the first category (they are highly leveraged, borrowing amounts many times their own capital to onlend them again) and, it seems, in many cases they look like members of the second group - and there is no way to know which (and banks often don't even know in which category they are themselves!). rdf provides a good analogy for what financial products look like these days, and how hard it has become to truly understand what they're worth, but what is even scarier is that the underlying assets that underpin all the financial bets made about them are turning sour, as the housing markets continues to fall and the economy grinds down to a halt.

So, while banks have frozen in the fear that they no longer understand what they and their colleagues have been doing, their core assets are turning bad and, in a chain reaction, will pollute all the financial bets made on them, ensuring that the banks' current fears turn to reality.

Banks are paralysed because they don't know how much bad stuff they have. Can it be better when they know that they really have a lot?

Thus the Paulson plan is unlikely to help much if it does not deal with the assets at the bottom of the toxic waste pile: not even the mortgages, but the houses themselves. The only way to do this would be to actually buy the houses, to prop up their prices, but this would cost rather more than $700 billion, and would bankrupt, for real, the government.

Fundamentally, house prices are out of whack with any realistic capacity of people to pay for them, and these must converge again. Apart from falling house prices (and the ensuing collapsing house of cars built on top of it), the only way to do this is to increase incomes - not those of people that own several homes, but rather of those that are trying to own one.

The bottom for houses, and for the banks, which fundamentally ride on them, will be reached when incomes - for the majority, not for the few - catch up with them. Governments should work on that, with simple ideas:

- re-regulate labor markets, in particular with increases in minimum wages, and with actual enforcement of existing rules;

- launch a massive public investment plan in, for instance, public transport infrastructure, housing thermal insulation and renewable energies;

- make banking boring by limiting leverage and eliminating banks that are "too big to fail";

- and increase marginal tax rates significantly to pay for it all.

Who knows, it might save a few banks - and investors - along the way.

Permalink | 394 comments